Inequality Regimes in Africa from Pre-Colonial Times to the Present

Inequality regimes in the African context

In recent years, the study of economic inequality has taken on a more global and historical perspective. Scholars such as Thomas Piketty, Branko Milanovic, and Walter Scheidel have challenged traditional ideas about the drivers of long-term trends in income and wealth distribution. This new global inequality literature has so far had little to say about Africa. Perhaps this is because available inequality estimates for Africa are patchy and the problem of persistent poverty was long deemed of greater importance than that of unequal distribution (Fosu 2015). In this space, overly simplistic narratives about inequality trends on the continent have taken hold. Pre-colonial African societies are portrayed as egalitarian due to their ‘traditional’ or ‘pre-capitalist’ economic structures characterized by land abundance and smallholder agriculture. The history of African inequality, so it is suggested, began with the co-evolution of colonialism and capitalism during the effective European occupation of Africa from circa 1900 to 1960, and the legacy of economic dualism and high inequality have persisted throughout the post-colonial era until today (Bigsten 2018, and for a more nuanced argument Van de Walle 2009).

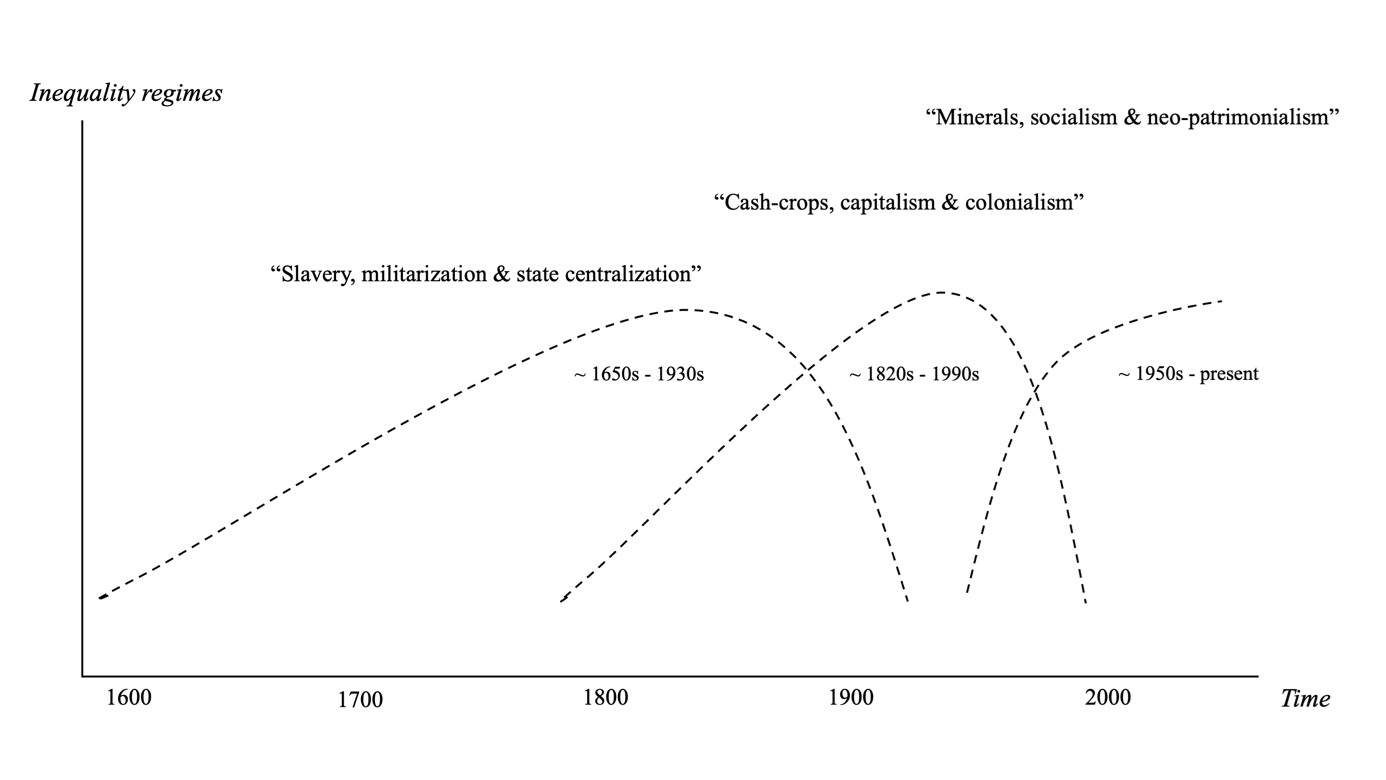

To understand inequality we should look at historical and present-day outcomes, such as Gini coefficients or top-income shares (Alvaredo et al 2021; Chancel et al 2023; Hillbom et al 2021), but also beyond them. The concept of “inequality regimes” was proposed by Piketty in Capital and Ideology. In our paper, we propose to extend its definition to encompass: 1) the institutions that legitimize a given distribution of economic resources; 2) the sources of income and wealth inequality, which include assets such as land, capital, and subsoil deposits, but also the control over human labor and rents, profits, and salaries; and 3) the social groups that obtain a disproportionate share of the pie and form the main beneficiaries of inequality. There have been at least three key inequality regimes in Africa since 1500, illustrated in Figure 1.

The slavery-based inequality regime

The first inequality regime we consider emerged from the rise of the transatlantic slave trade and the spread of plantation slavery across the continent. Enslaved people, slave-produced commodities, and control over trade routes were key sources of wealth and inequality during this wave. The main beneficiaries on the African continent itself were the slave-owning elites of large and powerful pre-colonial African states. The regime at large was underpinned by ideologies and institutions that enabled enslavement and the extraction of slave labor and other forms of ‘wealth in people’ (Guyer 1995). There is a lack of quantitative data to express pre-colonial inequality levels in the form of Gini coefficients or top income or wealth shares. But the intensification of the slave trade and the growth of internal slave markets are indicative of processes of unequal accumulation of ‘wealth in people’, the proceeds of the sale of human beings (such as consumer goods and weapons) and the fruits of enslaved labor (such as cash crops). Widespread slavery, therefore, is incompatible with the idea that pre-colonial Africa was dotted with egalitarian rural societies.

Figure 1. Illustration of shifting inequality regimes in Africa, 1600-present

Source: Authors’ own.

The colonial inequality regime

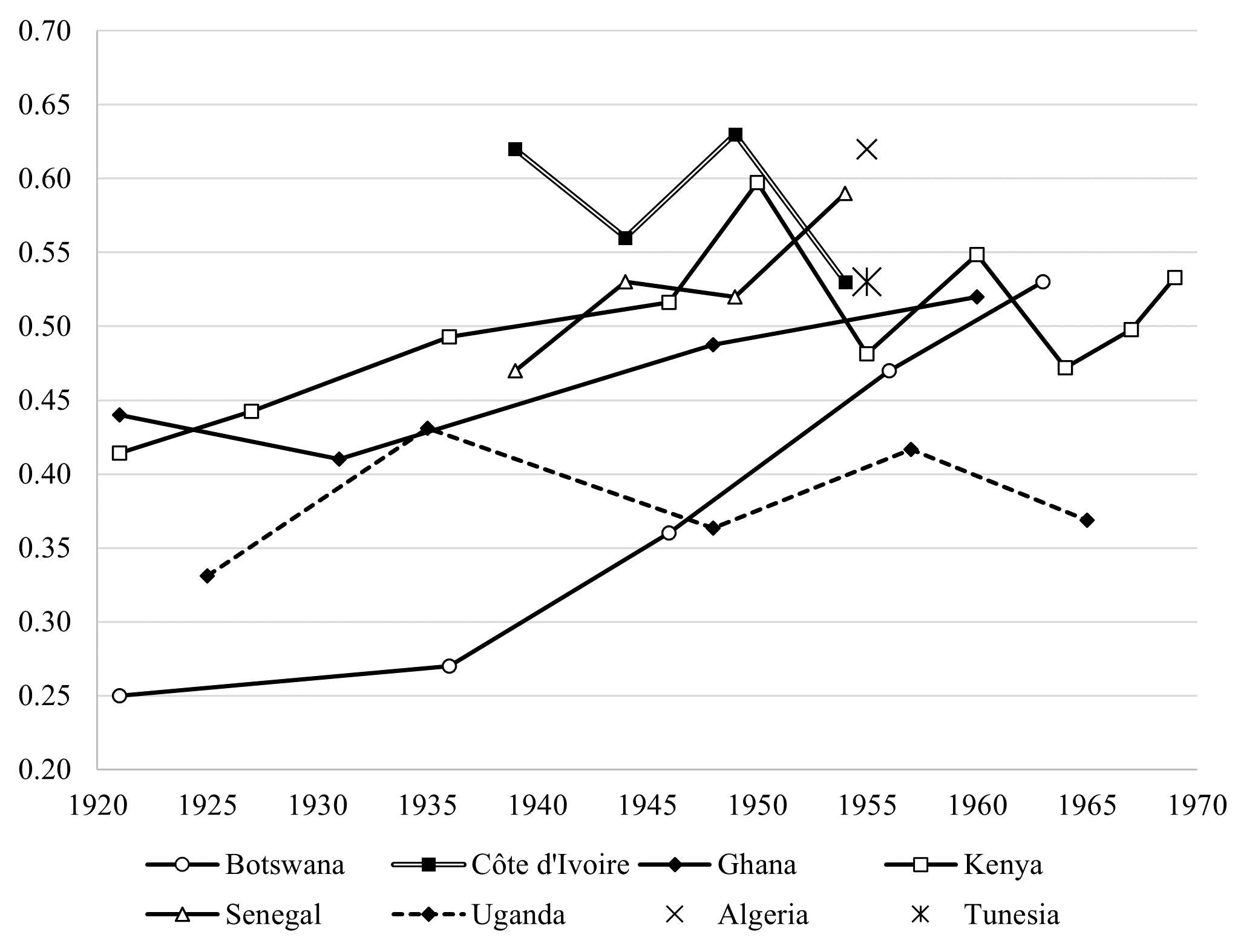

By the time slavery was abolished, income and wealth had become concentrated in the hands of European expatriates and settlers. Consequently a new regime of inequality emerged that was closely linked to the onset of colonial rule. Colonialism generated new forms of inequality, through the diffusion of capitalism and coercive institutions. Colonial inequality trends are shown in Figure 2. However, colonial inequality did not predominantly arise, as often claimed, from a dual economic system of ‘traditional’ versus ‘modern’ sectors. The notions of ‘dualism’ and ‘capitalism as a colonial invention’ are at odds with the historical evidence. Instead, households combining production for subsistence (‘traditional’) and the market (‘modern’) emerged as a key feature of Africa’s export-oriented agrarian colonial economies. This combination of subsistence-oriented and commercial farming, which involved farmers, traders, slaves, and migrant workers, emerged long before the colonial era. Evidence suggests that inequality rose during the latter half of the colonial era, but that the levels and trajectories across Africa were diverse. This diversity can be explained by the number of foreign settlers who controlled disproportionate shares of colonial export revenues or related public revenues, but also by the nature of the export sector. Capital-intensive commodities such as mining, cocoa, and coffee skewed the distribution more profoundly than labor-intensive commodities, especially annual crops like cotton and groundnuts (Hillbom et al 2021).

Figure 2. Income inequality estimates based on social tables for Algeria, Botswana, Côte d’Ivoire, Ghana, Kenya, Senegal, Tunesia, and Uganda, 1920–1970

Sources: Hillbom et al. (2021).

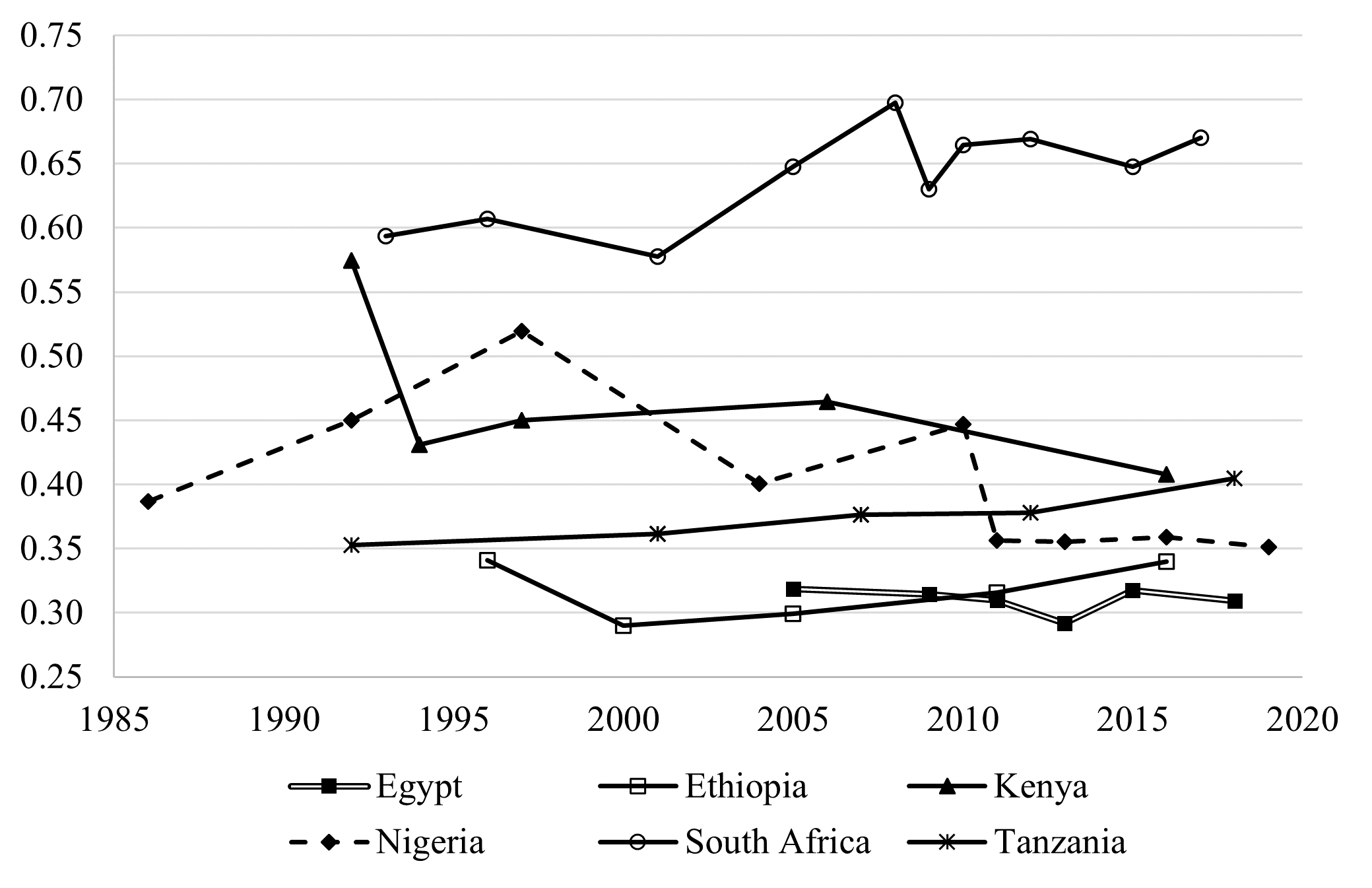

The diversity of post-colonial inequality paths

It’s often maintained that post-colonial Africa is characterized by high inequality. But there is large variation within the continent, as Figure 3 reveals. Given the variation in colonial inequality, and the many crises and policy shifts in the early post-independence era, such diversity should not come as a surprise. Post-independence, African countries transitioned to new inequality regimes of various sorts. In some places, such as South Africa, there was great continuity in terms of the institutions, sources of wealth and beneficiaries. In many other countries though, major ruptures took place after 1960. There were multiple drivers of such ruptures: the emigration of foreign settlers, the rise of African socialism, shifts in the sources of wealth from cash crops to minerals, including oil, and the outbreak of numerous civil wars.

Because of the prevalence of external shocks such as the slave trade, colonialism, and Cold War geopolitics, as well as the large number of countries, Africa offers myriad opportunities to evaluate the relative importance of evolutionary versus revolutionary forces of distributional change. That potential will be revealed once we move beyond the view that present-day African inequality is simply a persistent imprint of colonial capitalism and economic dualism.

Figure 3. Household expenditure Gini coefficients in six large African countries, 1985-2020

Source: UNU-WIDER World Income Inequality Database, version 30 June 2022.

References

Alvaredo, Facundo, Denis Cogneau, and Thomas Piketty (2021) ‘Income inequality under colonial rule: Evidence from French Algeria, Cameroon, Tunisia, and Vietnam and comparisons with British Colonies 1920–1960’, Journal of Development Economics, 152, pp. 1–20.

Bigsten, Arne (2018) ‘Determinants of the evolution of inequality in Africa’, Journal of African Economies, 27(1).

Chancel, Lucas, Denis Cogneau, Amory Gethin, Alix Myczkowski, and Anne-Sophie Robilliard (2023) ‘Income inequality in Africa, 1990-2019: Measurement, patterns, determinants’, World Development, 163.

Fosu, Augustin Kwasi (2015) ‘Growth, inequality and poverty in sub-Saharan Africa: Recent progress in a global context’, Oxford Development Studies 43(1), pp. 44–59.

Guyer, Jane (1995) ‘Wealth in people, wealth in things: Introduction’, Journal of African History 36(1), pp. 83–90.

Hillbom, Ellen, Jutta Bolt, Michiel de Haas and Federico Tadei (2021) ‘Measuring historical inequality in Africa: What can we learn from social tables?’ (Working Paper, African Economic History Network)

Piketty, Thomas (2020). Capital and ideology. Harvard University Press.

Van de Walle, Nicholas (2009) ‘The institutional origins of inequality in Sub-Saharan Africa’, Annual Review of Political Science, 12(1), pp. 307–327.

Cover image: Mansa Musa, Catalan Atlas. Bibliothèque Nationale de France.

This blog post was originally published on 5 December 2023 by Frontiers in African Economic History, the research blog of the African Economic History Network: